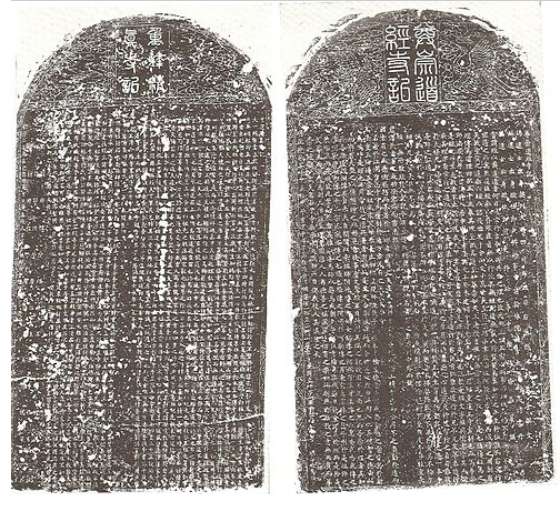

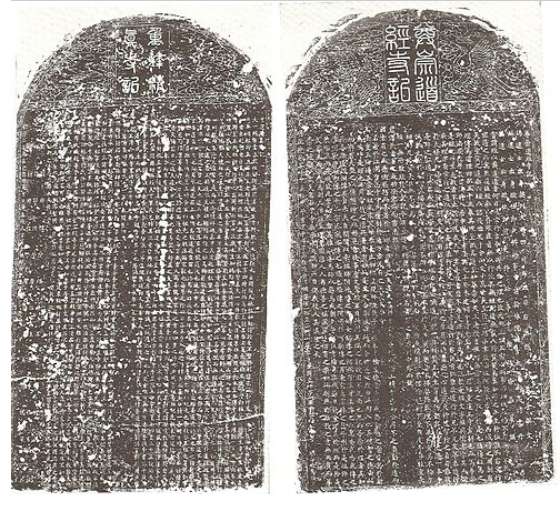

The Italian Jesuit Matteo Ricci became the first westerner to learn about the Jewish community of Kaifeng City, Henan Province, China when he was contacted by a Chinese-Jew named Ai Tian (艾田) in 1605 CE.[1] This discovery would lead to droves of religious and secular researchers visiting the community in the hopes of obtaining ancient, pre-Christian editions of the Old Testament, converting them to Christianity, or to just learn about their history in general.[2] The two most prominent theories as to why the Jews first came to China are that they arrived as religious refugees during the Han dynasty (206 BCE-221 CE), or as merchants during the Northern Song dynasty (960-1127). The main source for both theories ultimately derives from three stone inscriptions erected during the Ming and Qing Dynasties in the years 1489, 1512, and 1663 (sides A and B).[3] Additional sources come in the form of Chinese and foreign records ranging from the 8th-14th centuries. An analysis of all available evidence proves the ancestors of the Kaifeng Jews were merchants rather than refugees.

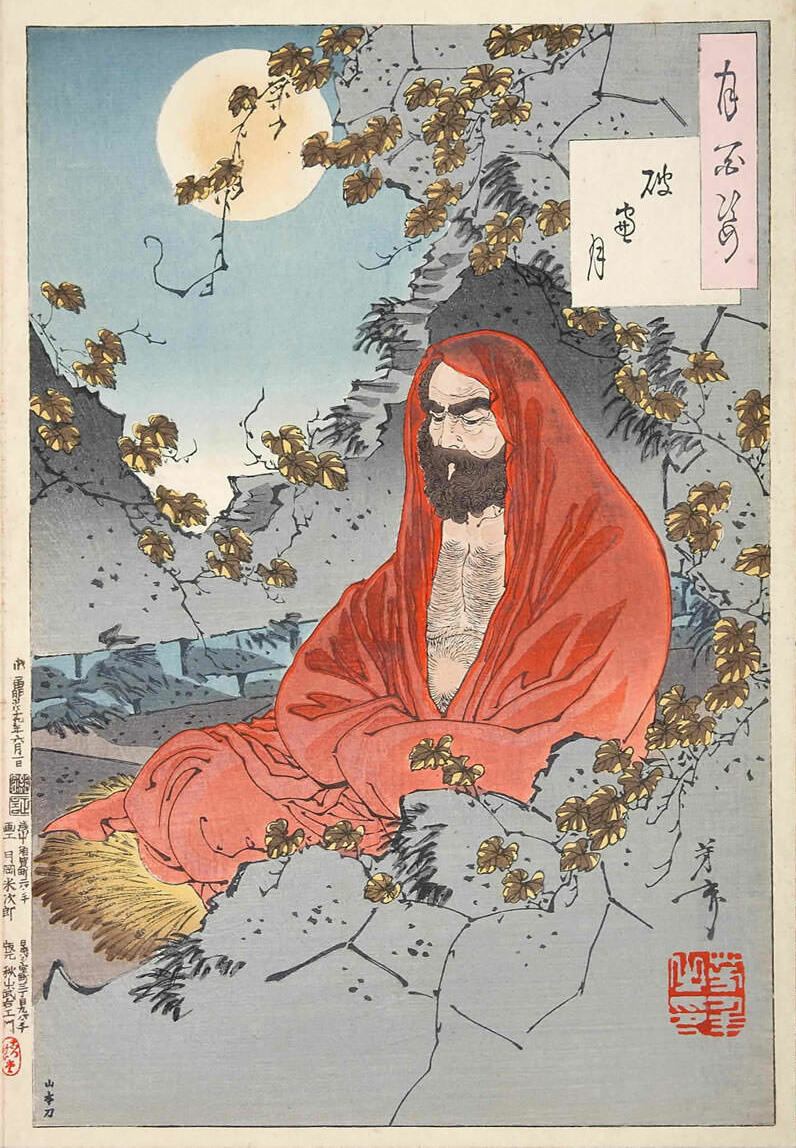

Matteo Ricci (1552-1610)

Proponents of the Han entry theory often cite a passage from the 1512 inscription which reads: “The founder of this religion is Abraham who is thus the ancestor. After him Moses, who transmitted the Scriptures, is thus the master of the religion. Then this same religion, from the time of the Han Dynasty, entered and established itself in the Middle Kingdom.”[4] The Jesuit Antoine Gaubil wrote in 1723 that the Jews had told him that they had been living in China for 1,650 years,[5] which would put their arrival shortly after the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem by the Roman Emperor Titus in 70 CE.[6] If true, this means the Jews fled from the Romans to China. Chen Yuan, however, felt it was actually Gaubil who had calculated the date to begin with, not the Jews.[7] Writing in 1770, one of Gaubil’s successors, Gabriel Brotier, noted in his memoir that the Jews had pinpointed the reign of Han Emperor Ming Di (漢明帝, r. 56-78 CE) as the time of their arrival.[8] When two Chinese Protestant converts visited the community in 1850, the Jews told them that they had brought Judaism to Kaifeng 1,850 years in the past.[9] Pan Guandan comments this predates Gaubil’s calculation by some 70 years, and places their entry during the reign of Han Emperor Ping Di (漢平帝, r. 1-6 CE).[10] Many late 19th and early 20th century researchers later built upon this foundation by pushing the date back to the earliest years of the Han.[11] Chen Yuan ultimately shot down the Han entry theory because the earlier 1489 inscription alludes to a later entry and because there is no physical evidence to support it. He writes:

"Yet in the more than one thousand years from Han to [Song,] if there were settlers of Jews , why have they not left a single trace of any person, event, or structure? Why does the [1489] inscription place the transmission of the religion in Song, and not before? The claim that the Kaifeng Jews are descended from those who came to China in Han is not credible. It is possible that some Jews reached China before Han, but the Jews in Kaifeng could not possibly descend from them.”[12]

In addition, if all three inscriptions are viewed chronologically, a pattern appears where later stones place the Jews arrival further and further back into history. For instance, the 1489 inscription quotes it was during the Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE), while the 1663A inscription says it was as far back as the early Zhou Dynasty (1045-256 BCE).[13] Wei Qianzhi believes this was the result of misreading part of a past inscription in the process of preparing a new one.[14] The 1489 and 1512 stones both state the Jewish patriarch Abraham established Judaism during the time period that coincided with the Zhou Dynasty.[15] This means that whoever prepared the 1663A inscription thought this implied the Jews had arrived in China during the Zhou. Michael Pollak suggests it was less of a mistake and more of a “protective maneuver” to cast an aura of antiquity in a land obsessed with ancient lineages.[16] This suggests the time was pushed back to the Han to make it seem like the Jews had settled in China long before they actually did. It may also be connected to religious apologetics (see below).

Despite this, Tiberiu Weisz, M.A., a retired Chinese language teacher and business consultant,[17] believes internal references to Jewish rituals and prayers in the inscriptions, as well as mentions of Semitic-looking people in ancient Chinese records points to a Han entry. The standard English translation of the inscriptions was completed in 1942 by the Canadian Anglican Bishop William Charles White, and it was based on a punctuated version of the original Classical Chinese script prepared by Chen Yuan. Weisz, however, felt it was time for a new translation because his own efforts yielded different readings,[18] and because White’s version had little to no references to Judaism at all.[19] After finishing, he cross-referenced information from the stones with religious scripture and Jewish and Chinese historical records. His research yielded a story that traced their history back to the destruction of the First Temple in Jerusalem and the exile of the Jews to Babylon in the 5th century BCE. After returning from the exile, a group of disenchanted Levites and Kohanim (Jewish Priests) parted with the biblical leader Ezra over a disagreement over a marriage proclamation and later settled in Northwestern India. Sometime prior to 108 BCE, these Jews had migrated to Ferghana in Central Asia where they were spotted by the Chinese General Li Guangli (李廣利). The Jews were then incorporated into the Han Empire when China annexed the region that would become Xinjiang in the last century before the Common Era. They continued to kneel during daily prayer, preserving the tradition in China long after Jews in the Holy Land discontinued the practice. Analyzing these claims individually requires a certain amount of digression, but this is necessary to put the Han entry theory to rest.

According to the Bible, King Artaxerxes I of Persia (465-424 BCE) gave Ezra permission to return to Israel with a large retinue of Jews who had been held in Babylonian captivity.[20] Upon their return, he learned that the common people and priestly class of Israel had violated the covenant with God by marrying pagan women and fathering children with them.[21] Ezra feared that these women would try to raise their sons as pagans, so he ordered all of the offenders to divorce their wives. The people submitted to this ruling, but there were still some dissenters: “Only Jonathan the son of Asahel and Jahzeiah the son of Tikvah stood up against this matter; and Meshullam and Shabbethai the Levite helped them.”[22] Weisz theorizes that this disgruntled bunch of Jews parted with Ezra and travelled to eastern lands where they remained cut off from the unfolding of Jewish history from that time forward.[23] The only problem is the inscriptions mention none of this.

Ink rubbings of the 1489 (left) and 1512 (right) stone inscriptions

Both the 1489 and 1512 inscriptions mention Ezra as being the last in a long line of prophets to receive transmission of “The Scriptures.”[24] This is because Ezra is thought by some to be the last editor of the

Torah—the storehouse of all Jewish Law.[25] By the time the Jews returned from exile, Judaism had changed from a religion based on the wisdom of ancient prophets to one relying on temple worship. Ezra shifted the focus back on the prophets by instituting the importance of

Torah study.[26] The 1512 inscription confirms: “Thereupon the religion of the ancestors was brilliant and renewed with brightness.”[27] Because of his efforts in reviving Judaism after the exile, Ezra is sometimes known as “The Father of Judaism.”[28] The 1489 inscription even refers to him as the “Patriarch of the Correct Religion.”[29] So there is absolutely no evidence to support the claim that the Kaifeng Jews had ever known Ezra, or had a falling out with him.[30]

All three of the inscriptions (1489, 1512, and 1663A) mention Judaism being transmitted from

Tianzhu (天竺),[31] a word long associated with India.[32] However, some scholars have voiced the opinion that it has a different contextual meaning. For example, Chen Yuan comments:

“Tianzhu is an ancient term. As used here it simply represented a place far to the west. In the same way Adam is compared to Pangu [in the inscriptions]. The purpose in both instances was to make the text comprehensible to people today…. So there was nothing wrong at the time in using Tianzhu to represent Judea.”[33]

Most importantly, the inscriptions never actually mention Jews traveling from India to China. They just state the religion originated in India. This is, of course, incorrect for Judaism originated in the land of Israel. The 1512 inscription actually uses the term

Tianzhu Xiyu (天竺西域).[34]

Xiyu has been used for centuries as an umbrella term to describe lands west of China, including those as far away as Egypt and Rome.[35]

Tianzhu Xiyu can be rendered several different ways. Under the context, I think White’s variation of “India of the Western Regions” lends itself to Chen’s view.[36] It could be read as “Judea of the Western Regions.”[37] My research shows there could be an additional reason for why they referred to India.

The Chinese have tried to find common ground between Buddhism, Daoism, and Confucian—the

Sanjiao (三教, Three Teachings)—ever since the Six Dynasties Period (220-589).[38] The well known phrase “Unity of the Three Teachings” (三教合一) was first used during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) to explain to the Mongol rulers that Buddhism, Daoism, and Confucianism were three different paths to the same goal. It later became its own philosophical school during the late Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).[39] The Jews knew of this concept themselves for the 1489 stone reads:

“When I ponder of the Three Religions [三教],

Each has temples where they honor their Lord.

The Confucians have the Dacheng Temple,

Where they honor and worship Confucius.

The Buddhists have the Shengrong Temple,

Where they honor Muniu [Shakyamuni Buddha].

The Daoists have the Yuhuang Temple,

Where they worship the Three Pures.

The Pure and Truth have the Israelite Temple,

Where they worship Huangtian [皇天].”[40]

Here, they defend the foreign nature of Judaism by comparing it to the three religions. In addition, the stones quote extensively from native Chinese classics not only to highlight similarities in philosophy with their own, but to appeal to their Confucian and Daoist neighbors.[41] They do not, however, quote from any Buddhist Sutras because Judaism is much closer in philosophy to Confucianism,[42] which disagrees on many points with the religion of the Buddha.[43] But if they were trying to appeal to the followers of all three religions, how would they connect Judaism to Buddhism? What better way to appeal to Buddhists than to say Judaism originated from India, the birthplace of Buddhism.[44] This is religious apologetics at its best. This means Chen Yuan’s suggestion from above is still valid because India was used to explain a foreign place outside of China in terms that would be familiar to the average Chinese person. This might also explain why the 1512 inscription pushed the Jews’ entry back to the Han. Buddhism first appeared in China during the 1st century BCE, which was during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE-221 CE).[45] Moreover, this would explain why the Jews told the Jesuit Gabriel Brotier in 1770 that they had originally arrived during the time of Han Emperor Ming Di (漢明帝, r. 56-78 CE). A popular legend appearing in the

Book of the Latter Han (後漢書, 5th cen.) states Buddhism was officially introduced to China after Ming Di dreamt of a “tall golden man,” who was later revealed to be the Buddha by his advisers.[46]

Weisz’s evidence for the Jews’ practice of kneeling during prayer comes from the 1663A inscription which reads: “Kneeling among those who prayed absolutely followed the rituals.”[47] He notes kneeling was common practice in ancient Jewish services during Ezra’s time, but it was shortly thereafter prohibited once Christianity adopted it into their ritual. Weisz reasons the Kaifeng Jews must have settled in Han China before the practice was banned.[48] Kneeling was indeed practiced prior to the fall of the Second Temple in Jerusalem,[49] but this is not, in my opinion, directly related to why the Kaifeng Jews continued to do it.

I would like to suggest a competing theory regarding synchronization between Judaism and Confucianism. Despite the ban, Jews were and still are allowed to kneel during services on the high holiday of

Yom Kippur (The Day of Atonement).[50] The Kaifeng Jews celebrated the equivalent of

Yom Kippur on the 10th day of the 6th moon and had several prayers books (

Siddur) set aside just for this occasion.[51] Kneeling on this holiday was probably strictly adhered to until Confucianism began to encroach on Kaifeng Judaism. As early as the 15th century, Jews began passing government exams to become Confucian

literati.[52] The 1489 inscription mentions bowing during prayer and making sacrifices to one’s ancestors.[53] The Jews may have initially equated their kneeling during

Yom Kippur and reverence for their ancestors on various holidays (

Passover,

Hanukah,

Purim, etc.) with the Confucian practice of bowing before and making sacrifices to ancestor tablets as a form of apologetics. But by the time of Jesuit Jean-Paul Gozani’s visit in 1704, the Jews were indeed emulating the latter. According to a letter from Gozani to another Jesuit:

“At our going out of the synagogue is a great hall, which I had the curiosity to look into. I saw nothing in it except a great number of incense bowls. They told me this was the place where they honored their Shêng-jê, or great men of their Law. The largest of these incense bowls, which is for the Patriarch Abraham, stands in the middle of the hall. After this stand those of Isaac, of Jacob, and his twelve children, called by them Shi-êrh-ko-p’ai-tzu, the Twelve Descendants or Tribes of Israel. Next are those of Moses, Aaron, Joshua, Ezra, and of several illustrious persons both men and women.

[…]

They added also, that in spring and autumn, they paid their ancestors the honours which are usually offered up to them in China, in the hall adjoining to their synagogues. They indeed did not offer up swine’s flesh, but that of other animals; and that, in the common ceremonies, they only presented china dishes filled with viands and sweetmeats, together with the incense; making very low bows and prostrations at the same time.”[54]

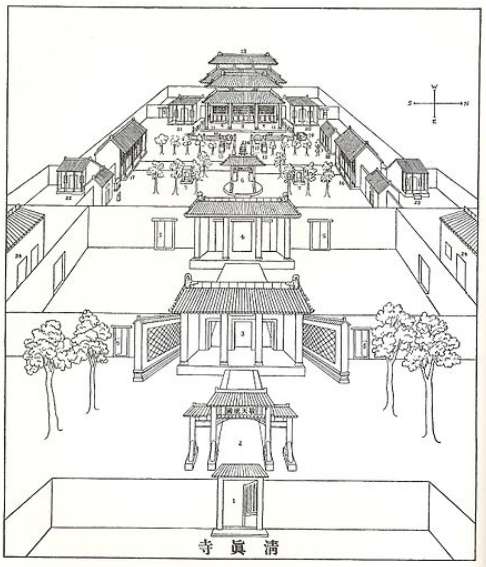

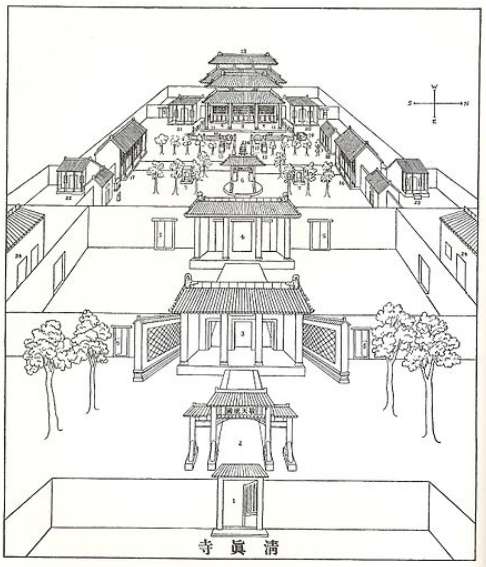

The Kaifeng Synagogue as it appeared in 1722.

This may have been a practice performed, at least by the Jewish-Confucian

literati, for some time prior to the early 17th century. This is because Ai Tian (艾田), a former

Juren graduate of the Confucian civil exams, knelt before pictures of what he mistakenly thought to be his Jewish ancestors in the Jesuit mission house when he visited Matteo Ricci in 1605.[55] By Gozani’s visit almost 100 years later, even the Chief Rabbi of Kaifeng was adhering to Confucian practices.

“There having been formerly (as at present) Bachelors, and Chien-shêng, who are a degree below Bachelors, I took the liberty to ask whether they worshipped Confucius. They all answered, and even their ruler [Chief Rabbi], that they honored him in like manner as the heathen literati in China; and that they partook with them in the solemn ceremonies performed in the halls of their great men.”[56]

What would make a once devoutly Jewish community adopt elements of a foreign religion? Song Nai Rhee believes the power and wealth of the Jewish-Confucian

literati gave them the influence to guide the direction their religion headed in.[57] It seems only natural that the Jews would be more willing to pepper their liturgy with Confucian practices given that these men were probably its main benefactors. Therefore, Kaifeng Judaism took on a thick patina of Confucianism, including the practice of kneeling more frequently than what traditional Judaism would have allowed. So the successive Chief Rabbis would have grown more and more accustomed to it until it was already fully accepted by the time of Gozani’s visit.

The evidence for the Jews living in Central Asia comes from Chinese records. Weisz quotes a passage from the book

History of Qin and Han Dynasties (秦漢史, 1988, 198) by Jian Bozan:

“It reached the outskirts of the remote Ferghana, beyond the Pamir Plateau. Originally that was the last undisturbed placed from the upheavals in the Northwest Central Asia and inhabited by people with 'deep eyes, big noses and (distinguished) headdress.' Their principal livelihood was growing grapes, grazing and raising horses. Although they had often seen Han emissaries coming and going in Central Asia, and they also knew that there was a Great Han country to the East, but because they had been under the control of the Huns for [a] very long time, they did not hold the Han emissaries to as a high esteem as those of the Huns (Xiongu)"[58]

He believes the people’s description of “deep eyes, big noses and (distinguished) headdress” proves a “small community” of Jews was discovered by the Han Dynasty General Li Guangli (李廣利) during his invasion of Central Asia in 108 BCE. Weisz notes the Chinese character used to designate the headdress can mean either ‘turban’ or ‘coiffure’.[59] When viewed from a Jewish context, he reasons the turban could be the miter-diadem combo worn by the Jewish Kohen-Priests (Exodus 28:36-38), or the coiffure could be the ear-locks worn by ancient Jews (Lev. 19:27). The biggest problem I have with this claim is that he automatically assumes the people were Jews. If he had at least tried to do a comparative study between Jews and the various tribes of Central Asia from this time and found more evidence to support his claim, his theory would be stronger. But as it stands, his only evidence is their appearance. The quoted passage is rather vague, and there is nothing particular about it that signals the people were Jewish. Given the time and place, the people could have easily been Persians, Sogdians, or even Indians for all we know.

The 123rd chapter of the

Records of the Grand Historian (史記, 90 BCE) reveals who these people were:

"Da Yuan (Ferghana) lies southwest of the territory of the Xiongnu, some 10,000 li directly west of China. The people are settled on the land, plowing the fields and growing rice and wheat. They also make wine out of grapes. The region has many fine horses … their forebears are supposed to have been foaled from heavenly horses. The people live in houses in fortified cities, there being some seventy or more cities of various sizes in the region. … The men all have deep-set eyes and profuse beards and whiskers. […]

The emperor had already taken a great liking to the horses of Da Yuan and ... he dispatched a party ... to go to the king of Da Yuan and ask him for some of the fine horses. ... Da Yuan by this time was overflowing with Han goods ... and at the end they refused to give the Han envoys any horses ... and they attacked and killed the envoys and seized their goods.

When the emperor received word of the fate of the envoys he was in a rage ... and he dispatched general Li Guangli with a force of 6,000 horsemen recruited from the dependent states, as well as 20,000 or 30,000 young men of bad reputation rounded up from the provinces and kingdoms, to launch an attack on Da Yuan. The title of Ershi General was given to Li Guangli because it was expected that he would reach the city Ershi and capture the fine horses there. … This was in the first year of the [Taichu] era (104 BCE)."[60]

Partial map of Alexander the Great's conquests in Central Asia and India. The City Alexandria Eschate (Alexandria the Furthest) is in the north in Ferghana.

Da Yuan (大宛) is considered by scholars to refer to Ferghana in Uzbekistan.[61] Alexander the Great is known to have founded the city of

Alexandria Eschate (Alexandria the furthest) in Ferghana where the modern city of Khojend stands during the 4th century BCE. It boasted a Greek population.[62] Considering their presence in Central Asia, some researchers claim

Yuan (宛) to be a transliteration of

Yawana, the ancient Persian and Indian word for the Greeks.[63] William Woodthorpe Tarn does not accept this, though, as there was a corresponding city in the Tarim Basin of China with no known Greek association called

Xiao Yuan (小宛). [64] However, he still believes the

Da Yuan people were of Greek origin. The Chinese explorer Zhang Qian (张骞, d. 114 BCE) traveled “postal roads” during his trip through Ferghana in 128 BCE. Tarn suggests the roads could have hypothetically been built by King Darius of Persia (c. 500 BCE) and maintained by local Greeks until the coming of Zhang Qian.[65] More conclusively, he believes

Da Yuan’s 70 walled cities were built by the Greeks since Alexander filled Bactria with such structures, and his enemies, the Achaemenids, only showed themselves capable of building low mudbrick ramparts in that area. Edwin G. Pulleyblank, on the other hand, believed they were Tuharans who had supplanted the Greeks in that area. He based this on a linguistic analysis of

Da Wan, a variation on their Chinese name.[66]

If this information is considered, three things become clear. First, Li Guangli’s push into Ferghana happened in 104 BCE, not 108 BCE. Second, the “small community” that Weisz speaks of was actually a large territory of 70 walled cities. In fact, Zhang Qian reported that its inhabitants numbered 300,000, which is not a paltry sum.[67] Third, these people were in fact not Jewish, but some other ethnic extraction. By far, the most serious problem is Weisz was fully aware that his source was referring to non-Jewish people. Jian’s book actually reads:

“Da Yuan was located beyond the Pamir Plateau, [it] originally was the last reserve in Northwest Central Asia for those Greeks [希臘人] with ‘deep-set eyes, big noses and profuse beards’ [多鬚]….”[68]

As can be seen, Weisz actually based his theory about the Jewish settlement in Central Asia on a mistranslation. The text mentions nothing about a “headdress,” only “profuse beards.” It would seem he confused the character of

xu (鬚, beard) with something else, possibly

jiu (鬏, coiffure).[69] Normally, mistranslating a character would be forgivable because even experts are entitled to make a mistake every once in a while. But the fact remains that Weisz underhandedly misquoted a source just so it would support his thesis. This is the final nail in the coffin for the Han entry theory.

Part 2 will come in a later entry.

Notes

[1] Xu Xin,

The Jews of Kaifeng, China: History, Culture, and Religion (Jersey City, NJ: KTAV Pub. House, 2003), 1-3.

[2] See for example Michael Pollak, “The Revelation of a Jewish Presence in Seventeenth-Century China: Its Impact on Western Messianic Thought.” in

The Jews of China: Volume I – Historical and Comparative Perspectives, ed. Jonathan Goldstein and Frank Joseph Shulman (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1999), 50-70.

[3] For more information on the inscriptions, see Donald Leslie,

The Survival of the Chinese Jews: The Jewish Community of Kaifeng (Tʻoung pao, 10. Leiden: Brill, 1972), 130-132. See also William Charles White,

Chinese Jews: A Complication of Matters Relating to the Jews of K’ai-Feng Fu, 2nd ed. (New York: Paragon Book Reprint, 1966), Part II, 7 and 57.

[4] White, Part II, 43. Compare with that: “Since the time of the Han / (ancestors) entered and settled in China” (Tiberiu Weisz,

The Kaifeng Stone Inscriptions: The Legacy of the Jewish Community in Ancient China (New York: iUniverse, 2006), 22.).

[5] James Finn,

The Jews in China: Their Synagogue, Their Scriptures, Their History, Etc. (London: Wertheim, 1843), 57.

[6] Peter Schafer,

The History of Jews in the Greco-Roman World: The Jews of Palestine from Alexander the Great to the Arab Conquest (Routledge, 2003), 129.

[7] Pan Guandan, “Jews in Ancient China—A Historical Survey,” in

Jews in Old China: Studies by Chinese Scholars, ed. Sidney Shapiro (New York: Hippocrene Books, 1988), 69.

[8] White, Part I, 66.

[9] White, Part I, 115.

[10] Pan, 69.

[11] Ibid, 70. Pan provides a comprehensive list.

[12] Ibid, 71.

[13] White, Part II, 11 and Weisz, 10.

[14] Wei Qianzhi, “Investigation of the Date of Jewish Settlement in Kaifeng,” in

The Jews of China: Volume 2 – A Sourcebook and Research Guide, ed. Jonathan Goldstein and Frank Joseph Shulman (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2000), 17.

[15] White, 8 and 43. See also Weisz, 4 and 22. The 1512 stone claims it originated in India during the Zhou, which is still outside of China.

[16] Michael Pollak,

Mandarins, Jews, and Missionaries: The Jewish Experience in the Chinese Empire (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1980), 259.

[17] “Tiberiu Weisz,” Filedby,

http://www.filedby.c..._weisz/707585/ (accessed July 21, 2011).

[18] The 1489 inscription mentions the Jews bringing a tribute of “Western Cloth” (possibly cotton) to the Song Court. An unnamed Song Emperor allows them to stay. White translates the dialogue as “…the Emperor said: ‘You have come to our China; reverence and preserve the customs of your ancestors, and hand them down at Bianliang (Kaifeng)” (White, Part II, 11). I changed the Wade-Giles to Pinyin. Weisz translates it as: “You

returned to my China…” (Weisz, 10). He claims this discrepancy comes from a past misreading of the Chinese character

gui (歸) that all other scholars have since followed. Considering the Jews were non-Chinese, Weisz supports his reading by citing a speech given by the future founder of the Ming Dynasty Zhu Yuanzhang (朱元璋, 1328-1398) to non-Chinese tribes. The people had formally lived under Chinese rule, but later fell under the jurisdiction of Barbarian overlords. In the speech, Zhu states: “Those who return (

gui) will find everlasting peace in China, and those who oppose us will find calamity beyond the borders” (Ibid, 11 n. 41). So if this usage of

gui is to be believed, then the emperor had to have known about Jewish settlements prior to the Song Dynasty (960-1279), thus supporting the Han entry theory. However,

gui has different meanings. Another sense of the word is allegiance or submission. For instance, Mencius IVA:9 reads: "得天下有道:得其民,斯得天下矣;得其民有道:得其心,斯得民矣;得其心有道:所欲與之聚之,所惡勿施,爾也。民之歸仁也,猶水之就下、獸之走壙也。故 為淵敺魚者,獺也;為叢敺爵者,鸇也;為湯武敺民者,桀與紂也。" D.C. Lau translates this as: “There is a way to win the Empire; win the people and you will win the Empire. There is a way to win the people; win their hearts and you will win the people. There is a way to win their hearts; amass what they want for them; do not impose what they dislike on them. That is all. The people turn to (歸) the benevolent as water flows downwards or as animals head for the wilds. Thus the otter drives the fish to the deep; thus the hawk drives birds to the bushes; and thus Jie and Zhou drove the people to Tang and King Wu" (D.C. Lau,

Mencius: A Bilingual Edition, rev. ed. (Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 2003), 159). Therefore, the use of “come” by White and Leslie (Leslie, 23) is still valid because it is referring to the Jews’ allegiance or submission to the Song emperor. Even the quote used by Weisz could be read in this context. I would like to thank CHF member Bao Pu for providing me with a list of classical works that use

gui in this way.

[19] Weisz, xii.

[20] “Ezra Chapter 7,” mechon-mamre.org,

http://www.mechon-ma...pt/pt35a07.htm (accessed July 21, 2011).

[21] “Exodus Chapter 34: Verse 15,” mechon-mamre.org,

http://www.mechon-ma...t/pt0234.htm#15 (accessed July 21, 2011).

[22] “Ezra Chapter 10: Verse 15,” mechon-mamre.org,

http://www.mechon-ma.../pt35a10.htm#15 (accessed July 21, 2011).

[23] Weisz, 69.

[24] White, Part II, 9 and 46 and Weisz, 3-5 and 28-29. The biblical figures Adam, Noah, and Abraham are mentioned among the prophets. The transliterations of their names connect them with deities from Chinese culture, such as Pangu, Nuwa, and Buddhist Louhans (Andrew H. Plaks, “The Confucianization of the Kaifeng Jews: Interpretations of the Kaifeng Stele Inscriptions,” in

The Jews of China: Volume I – Historical and Comparative Perspectives, ed. Jonathan Goldstein and Frank Joseph Shulman (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1999), 39-40.

[25] John Sailhamer,

The Meaning of the Pentateuch: Revelation, Composition, and Interpretation (Downers Grove, Ill: IVP Academic, 2009), 297.

[26] Ibid, 264-265.

[27] Weisz, 29 and White, Part II, 46. White even makes a point to mention: “The emphasis on the ‘renewed’ or ‘new’ brilliance points to the restoration of the Law and Ritual by Ezra” (White, Part II, 49 n. 20).

[28] Francis I Fesperman,

From Torah to Apocalypse: An Introduction to the Bible (Lanham: University Press of America, 1983), 171.

[29] Weisz, 5 and White, Part II, 9. Ezra has remained a most beloved prophet throughout the centuries. The Jewish historian Josephus wrote that Ezra died and was laid to rest in the city of Jerusalem (David Marcus, Haïm Z'ew Hirschberg and Abraham Ben-Yaacob, “Ezra,” in Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2nd ed., ed. Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik, vol. 6 (Detroit:: Macmillan Reference, 2007), 653). Hundreds of years later, however, a spurious tomb in his name was claimed to have been discovered in Iraq (see note #30) around the year 1050. The tombs of ancient prophets were believed by medieval people to produce a heavenly light. In his

Concise Pamphlet Concerning Noble Pilgrimage Sites, Yasin al-Biqai (d. 1095) wrote that the “light descends” onto Ezra’s tomb (Joseph W. Meri,

The Cult of Saints Among Muslims and Jews in Medieval Syria (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 23). Jewish merchants partaking in mercantile activities in India from the 11th-13th century often paid reverence to him by visiting his tomb on their way back to places like Egypt (S. D. Goitein,

A Mediterranean Society: The Jewish Communities of the Arab World as Portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Geniza – The Individual (Vol. 5) (Berkeley, Calif. [a.u.]: Univ. of California Press, 1999), 18). The noted Jewish traveler Benjamin of Tudela (d. 1173) visited the tomb and recorded the types of observances that both Jews and Muslims of his time afforded it. A fellow Jewish traveler named Yehuda Alharizi (d. 1225) was told a story during his visit (c. 1215) about a shepherd who had learned of its location in a dream 160 years before (hence the dating). He also commented the light that shown on the tomb was the “glory of God” (Meri, 21. See also Rabbi Petachia of Ratisbon,

Travels of Rabbi Petachia of Ratisbon, who in the latter end of the 12. century, visited Poland, Russia, Little Tartary, the Crimea, Armenia ...: translated ... by A. Benisch, with explanat. notes by the translat. and W. F. Ainsworth( London: Trubner & C., 1856), 91 n. 56). Working in the 19th century, Sir Austen Henry Layer suggested the original tomb had probably been swept away by the ever-changing course of the Tigris since none of the key buildings mentioned by Tudela were present at the time of his expedition (Austen Henry Layard and Henry Austin Bruce Aberdare,

Early Adventures in Persia, Susiana, and Babylonia, Including a Residence Among the Bakhtiyari and Other Wild Tribes Before the Discovery of Nineveh (Farnborough, Eng: Gregg International, 1971), 214-215). If true, this would mean the current tomb in its place is not the same one that Tudela and later writers visited. It continues to be an active holy site today (Raheem Salman, “Iraq: Amid War, a Prophet’s Shrine Survives,” LA Times blog, entry posted August 17, 2008,

http://latimesblogs....ad-amid-wa.html (accessed July 21, 2011)).

[30] The closest thing I can find alluding to a fallout between Ezra and a body of Jews is a legend circulating in the 19th century. According to the tradition, once Ezra returned to Jerusalem and the rebuilding of the Second Temple was completed, he sent communications to Jews in other parts of the Diaspora welcoming them back to the holy city. The Jews of Yemen refused on their belief that the Second Temple was sure to fall again. Because of this, Ezra angrily banned the Yemenites from ever entering Jerusalem. The Jews thereafter refused to name their sons Ezra in protest. In addition, God cursed Ezra never to be buried in Israel. He is said to have died in Iraq (See Tudor Parfitt,

The road to Redemption: the Jews of the Yemen; 1900 - 1950 (Brill's series in Jewish studies, 17. Leiden [u.a.]: Brill, 1996), 4 and Benjamin Lee Gordon,

New Judea; Jewish Life in Modern Palestine and Egypt (Philadelphia: J.H. Greenstone, 1919), 70). A spurious tomb in his name was claimed to have been found in Iraq in the year 1050 (see note #29 above).

[31] White, Part II, 11, 43, and 62 and Weisz, 10, 22, and 40.

[32] John E Hill,

Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes During the Later Han Dynasty 1st to 2nd Centuries CE : an Annotated Translation of the Chronicle on the 'Western Regions' in the Hou Hanshu (Charleston, South Carolina: BookSurge Publishing, 2009), 31 and 356-359.

[33] Chen Yuan, “A Study of the Israelite Religion in Kaifeng,” in

Jews in Old China: Studies by Chinese Scholars, ed. Sidney Shapiro (New York: Hippocrene Books, 1988), 23-24. The bracketed words are mine.

[34] White, Part II, 43 and Weisz, 22.

[35] See Hill, 23-27 and 254-310.

[36] White, Part II, pp. 43 and 48 n. 8. Weisz even interprets it as “Tianzhu, the Western Regions” (Weisz, 22). I altered the text slightly. White translates it as “India of the Western country.”

[37] It has even been suggested to me by Dror Weil of the National Taiwan Cheng-Chi University that

Tianzhu might be a scribal mistake for

Tian fang (天房, Heavenly Square), a term, according to him, used by Chinese Muslims to refer to the Middle East (personal communication, 12-23-09). However, this term seems to apply specifically to Arabia, the birthplace of Islam (Raphael Israeli,

Islam in China: Religion, Ethnicity, Culture, and Politics (Lanham, Md: Lexington Books, 2002), 18-19).

[38] Stephen Little and Shawn Eichman,

Taoism and the Arts of China (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2000), 27.

[39] Timothy Brook,

Praying for Power: Buddhism and the Formation of Gentry Society in Late-Ming China (Cambridge Mass: Council of East Asian Studies, 1993), 68. See also Timothy Brooke, “Rethinking Syncretism: The Unity of the Three Teachings and their Joint Worship in Late- Imperial China,”

Journal of Chinese Religions 21 (Fall 1993): 13-44.

[40] Weisz, 16 and White, Part II, 14.

[41] See, for example, Weisz, 3-4, 8-10, 18, 32-33, and 35- 41.

[42] The 1489 stone actually states: “Although the religion of Confucius and this / religion are similar as a whole and different in details, / Both are determined and set in ways” (Weisz, 17). See White, Part II, 14-15 for the difference. See also Leslie,

The Survival of the Chinese Jews, 97-98 and 100-102.

[43] William Theodore De Bary,

The Buddhist Tradition in India, China and Japan (New York: Vintage books, 1972), 126-127 and 131-138.

[44] Kaifeng Judaism was also known as the “Indian Religion” (

Tianzhu Jiao, 天竺教) (Leslie,

The Survival of the Chinese Jews, 18).

[45] Francis Wood,

The Silk Road: Two Thousand Years in the Heart of Asia (University of California Press, 2002), 93. Donald W. Mitchell states: “By the middle of the first century C.E., Buddhist monks were present in the Chinese capital, and the Buddha was worshipped at the imperial court as a god alongside Lao-tzu, the founder of Taoism, and another popular god named the Yellow Emperor” (Donald W. Mitchell,

Buddhism: Introducing the Buddhist Experience (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 199). This shows that it made leaps and bounds among the populace after its introduction.

[46] Hill, 31 and 363-364.

[47] Weisz, 35. See White, Part II, 60 for the difference in translation.

[48] Weisz, 7 n. 29 and 58

[49] Abraham Ezra Millgram,

Jewish Worship (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1971), 356-360.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Leslie,

The Survival of the Chinese Jews, 89, 91, 155-156.

[52] Ibid, 27.

[53] White, Part II, 10 and Weisz, 6-8.

[54] White, Part I, 41 and 43.

[55] Ibid, Part III, 16. You can read more about the

Juren (chu-jen) ranking in Charles O. Hucker,

A Dictionary of Official Titles in Imperial China (Taibei Shi: Nantian shu ju, 1988), 197.

[56] Ibid, Part I, 43. Gozani refers to the community’s religious leader as the “Ruler of the Synagogue” (40).

[57] Song Nai Rhee, “Jewish Assimilation: The Case of Chinese Jews,”

Comparative Studies in Society and History 15, no. 1 (Jan., 1973): 122-124.

[58] Weisz, 71.

[59] Ibid, 69.

[60] Sima Qian and Burton Watson,

Records of the Grand Historian 2 (Hong Kong [u.a.]: Columbia Univ. Press, 1993), 233 and 245-246. I altered the era name because the original stated “Taiyuan” is a typo.

[61] Hill, 167.

[62] Ibid, 167-169.

[63] Ibid, 167.

[64] William Woodthorpe Tarn,

The Greeks in Bactria and India (Cambridge University Press, 1966), 474. You can read more about

Xiao Yuan in Hill, 74-77 and 167.

[65] Ibid, 475-476.

[66] Hill, 170.

[67] A.F.P. Hulsewe, Michael Loewe, and Gu Ban.

China in Central Asia: The Early Stage, 125 B.C.-A.D. 23: An Annotated Translation of Chapters 61 and 96 of The History of the Former Han Dynasty (Leiden: Brill, 1979), 132.

[68] Jian Bozan, 《秦汉史》(

History of the Qin and Han Dynasties), (Zhongguo shi yan jiu cong shu. Taibei Shi: Yun long chu ban she, 2003), 198.

[69] I would like to thank Sun Wenjia for initially bringing my attention to the mistranslation in the text and suggesting possible characters that Weisz might have confused “beard” with. The translation I used was suggested by CHF member Tiger Tally. I have altered it slightly for readability.

Bibliography

Brook, Timothy.

Praying for Power: Buddhism and the Formation of Gentry Society in Late-Ming China. Cambridge Mass: Council of East Asian Studies, 1993.

----------“Rethinking Syncretism: The Unity of the Three Teachings and their Joint Worship in Late-Imperial China.”

Journal of Chinese Religions 21 (Fall 1993): 13-44.

Chen, Yuan. “A Study of the Israelite Religion in Kaifeng.” In

Jews in Old China: Studies by Chinese Scholars, ed. Sidney Shapiro, 15-45. New York: Hippocrene Books, 1988.

De Bary, William Theodore.

The Buddhist Tradition in India, China and Japan. New York: Vintage books, 1972.

“Exodus Chapter 34: Verse 15.” mechon-mamre.org.

http://www.mechon-ma...t/pt0234.htm#15 (accessed July 21, 2011).

“Ezra Chapter 7.” mechon-mamre.org.

http://www.mechon-ma...pt/pt35a07.htm (accessed July 21, 2011).

“Ezra Chapter 10: Verse 15.” mechon-mamre.org.

http://www.mechon-ma...pt35a10.htm#15 (accessed July 21, 2011).

Fesperman, Francis I.

From Torah to Apocalypse: An Introduction to the Bible. Lanham: University Press of America, 1983.

Finn, James.

The Jews in China: Their Synagogue, Their Scriptures, Their History, Etc. London: Wertheim, 1843.

Goitein, S. D.

A Mediterranean Society: The Jewish Communities of the Arab World as Portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Geniza – The Individual (Vol. 5). Berkeley, Calif. [a.u.]: Univ. of California Press, 1999.

Gordon, Benjamin Lee.

New Judea; Jewish Life in Modern Palestine and Egypt. Philadelphia: J.H. Greenstone, 1919.

Hulsewe, A.F.P., Michael Loewe, and Gu Ban.

China in Central Asia: The Early Stage, 125 B.C.-A.D. 23: An Annotated Translation of Chapters 61 and 96 of The History of the Former Han Dynasty. Leiden: Brill, 1979.

Hill, John E.

Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes During the Later Han Dynasty 1st to 2nd Centuries CE: an Annotated Translation of the Chronicle on the 'Western Regions' in the Hou Hanshu. Charleston, South Carolina: BookSurge Publishing, 2009.

Hucker, Charles O.

A Dictionary of Official Titles in Imperial China. Taibei Shi: Nantian shu ju, 1988.

Israeli, Raphael.

Islam in China: Religion, Ethnicity, Culture, and Politics. Lanham, Md: Lexington Books, 2002.

Jian, Bozan. 《秦漢史》(

History of the Qin and Han Dynasties). Zhongguo shi yan jiu cong shu. Taibei Shi: Yun long chu ban she, 2003.

Layard, Austen Henry, and Henry Austin Bruce Aberdare.

Early Adventures in Persia, Susiana, and Babylonia, Including a Residence Among the Bakhtiyari and Other Wild Tribes Before the Discovery of Nineveh. Farnborough, Eng: Gregg International, 1971.

Lau, D.C. Mencius: A Bilingual Edition, rev. ed. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 2003.

Leslie, Donald.

The Survival of the Chinese Jews: The Jewish Community of Kaifeng. T’oung pao, 10. Leiden: Brill, 1972.

Little, Stephen, and Shawn Eichman.

Taoism and the Arts of China. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2000.

Marcus, David, Haïm Z'ew Hirschberg, and Abraham Ben-Yaacob. “Ezra.” In Encyclopaedia Judaica. 2nd ed. Edited by Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik. Vol. 6. Detroit: Macmillan Reference, 2007

Meri, Joseph W.

The Cult of Saints Among Muslims and Jews in Medieval Syria . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Millgram, Abraham Ezra.

Jewish Worship. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1971.

Mitchell, Donald W.

Buddhism: Introducing the Buddhist Experience. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Pan, Guandan. “Jews in Ancient China—A Historical Survey.” In

Jews in Old China: Studies by Chinese Scholars, ed. Sidney Shapiro, 46-102. New York: Hippocrene Books, 1988.

Parfitt, Tudor.

The road to Redemption: the Jews of the Yeme ; 1900 - 1950. Brill's series in Jewish studies, 17. Leiden [u.a.]: Brill, 1996.

Petachia of Ratisbon, Rabbi.

Travels of Rabbi Petachia of Ratisbon, who in the latter end of the 12. century, visited Poland, Russia, Little Tartary, the Crimea, Armenia ...: translated ... by A. Benisch, with explanat. notes by the translat. and W. F. Ainsworth. London: Trubner & C., 1856.

Plaks, Andrew H. “The Confucianization of the Kaifeng Jews: Interpretations of the Kaifeng Stele Inscriptions.” In

The Jews of China: Volume I – Historical and Comparative Perspectives, ed. Jonathan Goldstein and Frank Joseph Shulman, 36-49. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1999.

Pollak, Michael.

Mandarins, Jews, and Missionaries: The Jewish Experience in the Chinese Empire. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1980.

---------- “The Revelation of a Jewish Presence in Seventeenth-Century China: Its Impact on Western Messianic Thought.” In

The Jews of China: Volume I – Historical and Comparative Perspectives, ed. Jonathan Goldstein and Frank Joseph Shulman, 50-70. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1999.

Sailhamer, John.

The Meaning of the Pentateuch: Revelation, Composition, and Interpretation. Downers Grove, Ill: IVP Academic, 2009.

Salman, Raheem. “Iraq: Amid War, a Prophet’s Shrine Survives.” LA Times blog. Entry posted August 17, 2008. (accessed July 21, 2011).

Schafer, Peter.

The History of Jews in the Greco-Roman World: The Jews of Palestine from Alexander the Great to the Arab Conquest. Routledge, 2003.

Sima, Qian and Burton Watson.

Records of the Grand Historian 2. Hong Kong [u.a.]: Columbia Univ. Press, 1993.

Song, Nai Rhee. “Jewish Assimilation: The Case of Chinese Jews.”

Comparative Studies in Society and History 15, no. 1 (Jan., 1973): 115-126.

Tarn, William Woodthorpe.

The Greeks in Bactria and India. Cambridge University Press, 1966.

“Tiberiu Weisz.” Filedby.

http://www.filedby.c...u_weisz/707585/ (accessed July 21, 2011).

Schafer, Peter.

The History of Jews in the Greco-Roman World: The Jews of Palestine from Alexander the Great to the Arab Conquest. Routledge, 2003.

Sima, Qian and Burton Watson.

Records of the Grand Historian 2. Hong Kong [u.a.]: Columbia Univ. Press, 1993.

Song, Nai Rhee. “Jewish Assimilation: The Case of Chinese Jews.”

Comparative Studies in Society and History 15, no. 1 (Jan., 1973): 115-126.

Tarn, William Woodthorpe.

The Greeks in Bactria and India. Cambridge University Press, 1966.

“Tiberiu Weisz.” Filedby.[url]

http://www.filedby.c...u_weisz/707585/ (accessed July 21, 2011).

Wei, Qianzhi. “Investigation of the Date of Jewish Settlement in Kaifeng.” In

The Jews of China: Volume 2 – A Sourcebook and Research Guide, ed. Jonathan Goldstein and Frank Joseph Shulman, 14-25. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2000.

Weisz, Tiberiu.

The Kaifeng Stone Inscriptions: The Legacy of the Jewish Community in Ancient China. New York: iUniverse, 2006.

White, William Charles.

Chinese Jews: A Complication of Matters Relating to the Jews of K’ai-Feng Fu, 2nd ed. New York: Paragon Book Reprint, 1966.

Wood, Francis.

The Silk Road: Two Thousand Years in the Heart of Asia. University of California Press, 2002.

Xu, Xin.

The Jews of Kaifeng, China: History, Culture, and Religion. Jersey City, NJ: KTAV Pub. House, 2003.