(I originally wrote this in April of this year. Again, the blog will not let me display large images, so I posted a link below.)

The Buddhist monk Bodhidharma (菩提達摩, a.k.a. Damo, 達摩) is said to have come to China during the 6th century in order to spread his own form of meditation-based Mahayana Buddhism known as Chan (禪), or as it is more widely known, Zen. The common story passed around in martial arts circles is that the Indian monk retired to a cave near the Shaolin Monastery where he meditated for nine years. During this time, his concentration was so strong that either: 1) his image was burnt into the living rock or 2) his gaze burnt a hole in the rock. After his period of reflection was over, he saw the monks of Shaolin were too physically weak to handle the rigors of lengthy meditation, so he, in the words of Master Wong Kiew Kit: “taught them a series of external exercises known as the Eighteen Lohan Hands, and a system of internal exercises known as the Classic of Sinew Metamorphosis.” [1] Kit believes generals who retired to the Monastery later developed the external exercise into a fighting system, and the internal exercises became Shaolin Qigong. [2] Other legends flat out claim Bodhidharma was the creator of Shaolin kung fu. There is even a Chinese film dedicated to his life and later creation of kung fu in China. [3]

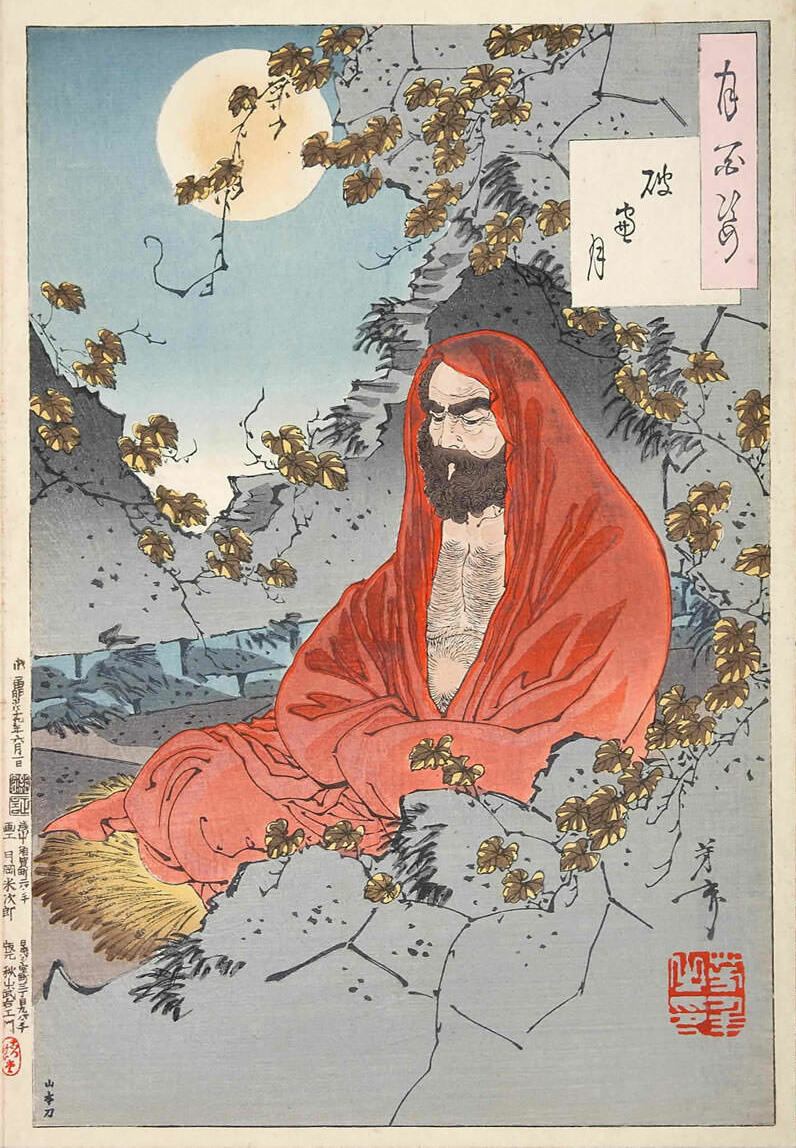

A 19th century Japanese woodblock print of Bodhidharma by Yoshitoshi.

These legends are actually based on information derived from a qigong manual entitled Yijin Jing (易筋經). This is commonly translated into English as the “Muscle-Changing Classic,” “Tendon-Changing Classic,” “Muscle-Metamorphosis Classic,” etc. The manual has two prefaces purportedly written by two Chinese generals of different eras. The first preface by Tang Dynasty General Li Jing (李靖, 571- 649) tells the story of Bodhidharma’s seclusion in the cave for nine years and how the monks later found two books written by him inside an iron chest after his death. The first manual, Xisui Jing (洗髓經, Marrow-Washing Classic), was taken by his most senior disciple Huike (慧可) and disappeared. The second manual, the Yijin Jing, was coveted by the monks even though they could not fully understand the Sanskrit text. Sometime later, a monk tracked down the famous Indian holy man Paramiti who was able to translate it in full. After 100 days of practice, the monk gained an immortal body capable of living 10,000 eons. [4] The manual later disappeared until it was passed on to Li Jing by the hero Qiuran ke (虯髯客, the Curly-Bearded Stranger) during the 7th century. [5] The second preface by Song Dynasty General Niu Gao (牛皋) tells how he met a mysterious monk who had been the childhood teacher of his superior officer General Yue Fei (岳飛, 1103-1142). The monk passed Niu a letter and then magically vanished “to the West, to look for Master Bodhidharma.” [6] Yue read the letter which warned him of the fate that awaited him (execution on trumped up charges) if he returned to the capital. But being loyal to the end, Yue decided to return anyway. He gave Niu his copy of the manual before leaving. Niu buried the manual because he didn’t know anyone who was “capable of becoming a Buddha.” [7]

Unfortunately, the prefaces were written centuries after these generals died. There are many anachronistic mistakes and flat out fictions that point to this. I will list some of them:

* Li Jing’s preface is dated 628, but the Indian holy man Paramiti (fl. 705), who is said to have translated the Yijin Jing from Sanskrit into Chinese years before the general received it, wasn’t active until much later. [8]Analysis of outside sources show Bodhidharma had no historical connection to the monastery or the development of its martial arts during his life time. According to Prof. Meir Shahar:

* A battle formation said to have been utilized by Li Jing in the first preface comes from Ming Dynasty fiction. [9]

* The hero Qiuran ke (虯髯客) is actually a popular fictional character from a 10th century Chinese tale called “The Curly-bearded Stranger.” Li Jing is a prominent character within the narrative. [10]

* Niu Gao’s preface is dated 1142, but he refers to Emperor Qinzhong (欽宗), a posthumous temple name that was not bestowed until 1161. [11]

* Yue Fei’s family and state memoirs do not mention him studying under a monk. He did study under two men with possible military backgrounds, but records do not allude to them having any affiliation with Buddhist monasteries. [12]

In the sixth-century Record of Buddhist Monasteries in Louyang (Luoyang qielan ji) (ca. 547), [Bodhidharma]* is said to have visited the city, but no allusion is made to the nearby Mt. Song[, where Shaolin is located]. Approximately a century later, the Continuation of the Biographies of Eminent Monks (Xu Gaoseng zhuan) (645), describes him as active in the "Mt. Song-Luoyang" region. Then, in such early eighth-century compositions as the Precious Record of the Dharma's Transmission (Chuanfa baoji) (c. 710) Bodhidharma is identified not merely with Mt. Song but more specifically with the Shaolin Monastery, where supposedly for several years he faced the wall in meditation. [13]There is no way Bodhidharma could have taught the monks martial arts or even written the two manuals if Chinese records do not attest to his presence at Shaolin during his own lifetime. As far as martial arts are concerned, researchers have analyzed documents going back 250 years, and there are some that mention both Bodhidharma and Shaolin martial arts, but never connect the two. [14] In fact, the idea of the Zen patriarch physically teaching monks martial arts did not come about until the publishing of a highly popular satirical novel entitled The Travels of Lao Can (老殘遊記) in a magazine between 1904 and 1907. The author apparently confused the qigong attributed to Bodhidharma with martial arts. This mistake was then echoed in the proceeding novel Shaolin School Methods published in a newspaper serial in 1910, and an altered reprint in 1915 called Secrets of Shaolin Boxing. It spread into popular books and manuals on the subject from there, and into the public consciousness. [15]

* The bracketed words are mine.

So if Bodhidharma didn’t write it, who did? Researchers have suggested two different people. In a series of articles appearing in Black Belt Magazine during the 1960’s William Hu stated physical copies of the manual could not be traced back any further than the mid-19th century. He also claimed the author was a provincial governor of Hubei called Pan Wei (潘蔚), who was apparently adept in Chinese medicine and qigong. Pan published his version of the Yijin Jing under the title Weisheng Yaoshu (衛生要術, Essential Techniques for Guarding Life) in 1858. Hu explained the manual did not mention Bodhidharma, and that Pan himself likened the Muscle-Changing qigong to a Daoist exercise. [16] The only problem with Hu’s study is that he did not have access to all versions of the Yijin Jing, some of which predate Pan’s work. The earliest known extent version possible derives from the 17th century. The manual carries a comment which reads: “Stored at the Narrating-Antiquities Library of Qian Zunwang.” [17] This may refer to a certain Qian Ceng (錢曾), with the style name of Zunwang (尊王), who is recorded to have lived from 1629-1701. This version has an undated postscript by a person with the penname Zining Daoren (紫凝道人, Purple Coagulation Man of the Way), who lived on Mt. Tiantai in Zhejiang province. [18] His name appears on several of the proceeding versions. An 1825 edition dates his postscript to 1624, [19] lending credence to a version of it being in Qian Ceng’s library. Based on the penname, Zining Daoren could be either a Daoist or Buddhist because the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) was a time of synchronization between the “three religions.” [20] The reason that most current researchers believe he was a Daoist and that he was the true author is because: 1) the Muscle-Changing qigong is Daoist in nature since it is comprised of Daoyin (導引, guiding and stretching) exercises, not to mention the fact that it goes against the Buddhist concept of impermanence since the end result is an immortal body; 2) the Chinese have a habit of attributing newer works to famous sages. For example, there are verified Daoist works that attribute various other qigong exercises to Bodhidharma, some as far back as the 12th century. [21]

The monks of Shaolin have worshiped the Vajrapani Bodhisattva as their patron saint for over a thousand years. Literary and stelae evidence from the 8th and 16th century shows the monastery originally venerated him as the source of their martial strength and staff skills as well. An anecdotal story appearing in Zhang Zhuo's (張鷟. 660-741) Tang anthology tells of how the Shaolin monk Sengchou (僧稠, 480-560) gained supernatural strength and boxing skills after being force-fed raw meat by Vajrapani. [22] A stele dedicated in 1517 illustrates the story of how Vajrapani, disguised as a lowly monk, transformed into a mountain-striding giant wielding a fire poker as a staff in order to defend Shaolin from the Red Turban army during the Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368). [23] Stan Henning believes this story was created as both a decoy to hide the monk’s historical defeat at the hands of the Red Turban rebels, and to give a mythical origin for their famous staff method. [24] Nevertheless, this shows the monks considered someone else to be the originator of their skills centuries before Bodhidharma.

People who willingly choose to ignore the above information tend to cite the fact that even the current Shaolin abbot has mentioned Bodhidharma creating kung fu in interviews. I believe I know how the monks came to accept a new in-house origin myth. First and foremost, monks can’t have children after taking the tonsure, so the monastery must get staff from amongst the common folk the satirical novel and martial manuals mentioning the legend circulated. This means those people outside the monastery would be more likely to accept the legend than those already in it. Second, because the monastery has a rotation of new people, the “collective memory” of the sangha (Buddhist community) tends to differ from generation to generation. For example, the monks wove a wicker statue of Vajrapani’s Yaksha-like King Jinnalou (緊那羅王) form during the 17th century. One hundred years later, the monks of the new generation believed that Vajrapani himself had made it. [25] Third, Shaolin chose the wrong side in a political dispute, which led to the dispersal of the sangha when the monastery was burnt by a warlord in 1928. Fourth, the Shaolin cult of Vajrapani received a huge blow when the aforementioned statue perished in the fire. The cult was not rejuvenated until almost sixty years later when the monks rebuilt the shrine to him in 1984. [26] By the time the monastery was rebuilt and a newer sangha was formed, the Vajrapani legend had all but been forgotten. The younger and more prevalent myth about Bodhidharma won out in the end thanks largely to its proliferation amongst the common folk outside the monastery. To my knowledge, no one has ever tried to explain this before.

There is mixed sentiment towards debunking such myths among martial arts practitioners. On one end of the spectrum, there are some who are greatly offended to the point of anger. For example, during the 1920s and 30s the noted martial arts practitioner and historian Tang Hao (唐豪, 1897-1959) was the first person to seriously call into question the myths concerning Bodhidharma and the Daoist Immortal Zhang Sanfeng (張三丰). [27] A memorial essay about Tang by his friend and fellow martial artist Gu Liuxin (顧留馨) states: “Unhealthy factors such as ridiculous descriptions of Chinese martial arts which included outright fabrications, fantastical stories of Taoist fairies and immortals and strange Buddhist folktales corrupted and tainted people’s thoughts about Chinese martial arts. Tang Hao was merciless in his exposure of such tales and was extremely harsh in his critiques.” [28] This offended the long standing Confucian family-based lineage system where in martial artists thought of their masters and grandmasters as “fathers” and “grandfathers.” Therefore, a lot of people were upset when Tang’s book Study of Shaolin and Wudang (少林武當考, 1920) came out claiming their lineage patriarchs had no connection to martial arts at all. So upset it seems, as Gu Liuxin remembered, “some ruthless and self-proclaimed practitioners of Wudang and Shaolin made a plan to attack Tang Hao and beat him up.” [29] Tang was able to avoid this possibly lethal confrontation only because his friend Zhu Guofu (朱国福), a famous practitioner of Chinese and western boxing, negotiated an agreement where Tang left Nanjing for Shanghai. [30] On the other end of the spectrum, there are some who feel the “art” of martial arts is more important than the legends. I would say most of the practitioners that I have interviewed fall in the middle somewhere. Many of them are either unaware of the scholarly research into the subject, or they just simply refuse to accept it (without out reading anything!) because it goes against what they have been told by the senior members of their martial arts community. They feel generations of oral transmission trumps decades of solid research. They also seem to be under the impression that the scholarly consensus comes only from western researchers with zero martial arts experience. This couldn’t be farther from the truth.

There is also mixed sentiment among martial arts historians. In a paper entitled "Theater of combat: A critical look at the Chinese martial arts," Prof. Charles Holcombe warns: “If it is necessary to debunk the Bodhidharma myth since it is historically false, we must also be wary of our modern materialist impulse to tear aside the veil of myth to uncover the real martial arts beneath. The truth is that for most Chinese practitioners of the arts the myths were real enough.” [31] In a rebuttal paper, "On Politically Correct Treatment of Myths in the Chinese Martial arts," Stan Henning claims the statement was directed at him because of his own efforts to separate the myth from the art, and counters by highlighting the pioneering research of Tang Hao, thus illustrating that this is not a recent phenomenon. [32] In addition, Henning chastises him for accepting Chinese martial arts as a religious practice as opposed to its historical association with the military. He concludes by saying: "The bottom line is, polite deference to the myths surrounding the Chinese martial arts is not only unwarranted but also unworthy of serious scholarship. It is high time that self-styled American martial arts “scholars” [i.e. Holcombe] took a big step forward out of the 1920’s and up to the threshold of the 21st century." [33] I stand with Henning on this matter. I would also argue against Holcombe's stance by stating it is our duty as historians to record the past accurately for posterity. Bowing out to tradition will only cause the true history to be forgotten.

Notes

[1] Kiew K. Wong, The Art of Shaolin Kung Fu: The Secrets of Kung Fu for Self-Defense Health and Enlightenment (Boston, Mass: Tuttle, 2002), 19.

[2] Ibid.

[3] “Bodhidharma the founder of Shaolin Kung Fu,” Youtube, è©æ达摩 1 Bodhidharma the founder of Shaolin Kung fu è©æé”æ‘© 1 - YouTube (accessed July 21, 2011).

[4] I have not seen the original Chinese for this text. If the "eon" it refers to is the Buddhist "Kalpa" (劫)—this would be appropriate since the manual is attributed to a Buddhist saint—then a person would live a very, very long time. Tradition states a single Kalpa is 432 million years long (William Edward Soothill and Lewis Hodous, A Dictionary of Chinese Buddhist Terms: With Sanskrit and English Equivalents and a Sanskrit-Pali Index (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 2000), 232). So a person living 10,000 eons would be 4.3 trillion years old! To put things in perspective, scientists believe the earth is currently 4.3 billion years old. You would be 1,000 times older than the Earth.

[5] Meir Shahar, The Shaolin Monastery: History, Religion, and the Chinese Martial Arts (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2008), 165-167.

[6] Ibid, 169.

[7] Ibid, the full translation is on 168-170.

[8] Ibid, 168.

[9] Ibid, 170.

[10] Ibid, 168. For a brief synopsis of this character's tale, see James J.Y. Liu, The Chinese Knight Errant (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1967), 87-88. A full translation can be read in Yang Xianyi and Gladys Yang, Selected Tang Dynasty Stories (Foreign Language Press, 2000), 181-195.

[11] Ibid, 170.

[12] Edward Harold Kaplan, “Yueh Fei and the Founding of the Southern Sung” (Ph.D. Diss., University of Iowa, 1970), 10-11.

[13] Shahar, 13.

[14] Stan Henning and Tom Green, "Folklore in the Martial Arts" in Green, Thomas A. Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia (Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO, 2001), 129.

[15] Stan Henning, "Ignorance, Legend, and Taijiquan," Journal of the Chen Style Taijiquan Research Association Of Hawaii 2, no. 3 (Autumn/Winter 1994), 4-5.

[16] William Hu, "Research Refutes Indian Origin of I-Chin Ching," Black Belt Magazine 3, no. 12 (December 1965): 48 and 50.

[17] Shahar, 203.

[18] Ibid, 162 and 203.

[19] Ibid, 204.

[20] Daoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism. See the full chapter on “gymnastics” in Ibid, 137-181.

[21] Ibid, 171-172.

[22] Ibid, 35-36.

[23] Ibid, 83-92.

[24] Stan Henning, “Martial Arts Myths of Shaolin Monastery Part I: The Giant with the Flaming Staff,” Journal of the Chenstyle Taijiquan Research Association of Hawaii 5, no. 1 (1999): 2.

[25] Shahar, 88.

[26] Ibid.

[27] See the chapter “Chinese Martial Arts Historians” in Brian Kennedy and Elizabeth Guo, Chinese Martial Arts Training Manuals: A Historical Survey (Berkeley, Calif: North Atlantic Books, 2005), 38-60.

[28] Ibid, 47-48.

[29] Ibid, 49.

[30] Ibid, 50.

[31] Charles Holcombe, “Theater of combat: A critical look at the Chinese martial arts” in Combat, Ritual, and Performance Anthropology of the Martial Arts, ed. David E. Jones (Westport, Conn: Praeger, 2002), 158.

[33] Stan Henning, "On Politically Correct Treatment of Myths in the Chinese Martial arts," Journal of the Chen Style Taijiquan Research Association Of Hawaii 3, no. 2 (Summer 1995): 1.

[32] Ibid, 3.